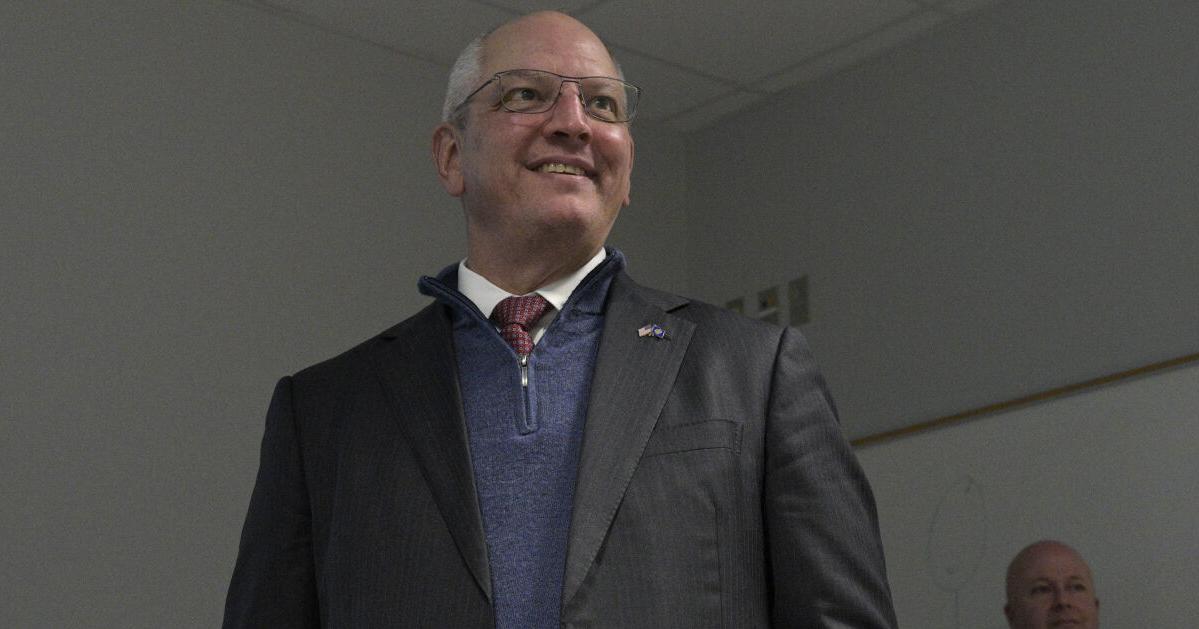

The crowd stood and applauded when Gov. John Bel Edwards was announced as the next speaker when the recent expansion of the LSU Medical School in Shreveport was unveiled.

Speaker after speaker praised Edwards for overseeing a dramatic improvement in Louisiana’s finances over his eight-year tenure, a boost that allowed state construction dollars to help finance the $79 million Center for Medical Education.

“You, sir, will go down in the annals with those other men who have invested in higher education over time, especially in the American South,” said LSU Chancellor William Tate IV.

The Dec. 11 event represented a culmination of Edwards’ governing philosophy — that the tax increase he pushed through the Legislature during his first year in office would balance the budget and provide the money needed to improve colleges, universities and K-12 schools; to upgrade roads and bridges and to keep towns and cities safer.

These investments, Edwards pledged, would create more jobs by producing better-educated workers, by making it easier for people and goods to travel throughout the state and by creating pathways to success for troubled youth.

The approach differs from that of Attorney General Jeff Landry, the Republican who was elected governor in October after promising that lower taxes, less government regulation and more incarceration of troublemakers would create jobs and make Louisiana safe.

Edwards, a Democrat, believes that his ideas promise a better future for Louisiana.

“When I leave office, the state of Louisiana will be better than it was when I took office,” the 56th governor has said repeatedly in recent days.

He notes that Louisiana has its lowest unemployment rate, its highest gross domestic product, its highest personal income and a rate of uninsured residents that is below the national average after he expanded Medicaid to the working poor. The state is beginning to rebuild its coast and long-neglected infrastructure projects throughout Louisiana have been completed or are underway.

What’s more: Edwards inherited a $2 billion budget deficit from Republican Gov. Bobby Jindal and is leaving Landry with $3.2 billion in reserves after balancing the budget year after year without gimmicks.

“I think that he’s the best governor of my lifetime, which covers a lot of territory,” said James Carville, a 79-year-old Democratic strategist who lives in New Orleans.

But other analysts who take the long view have nagging concerns that Edwards’ successes will provide only a temporary lift for a poor, woefully educated state that has remained at the bottom of too many national economic and social rankings.

Landry, for example, could give away the budget surplus, just as Jindal did with the smaller surplus he received from his predecessor, Gov. Kathleen Blanco.

“John Bel Edwards has represented the state well, but I don’t see him as a transformational governor,” said Tim Landry, a doctoral candidate in history at LSU.

Bob Mann, an LSU communications professor and author who worked for Democratic elected officials, also doesn’t believe that Edwards has changed the state’s trajectory.

“Despite his successes and his relative popularity, he leaves with the state entirely in Republicans’ hands,” Mann said. “By that standard — and I would say it’s the most important standard when considering this question — it’s impossible to consider him transformational in any serious way.”

Progress made

The son, grandson and great-grandson of sheriffs in Tangipahoa Parish, Edwards seemed to have little chance to make the leap from the state House to the Governor’s Mansion when he ran for governor in 2015. He was a little-known Democrat in a state that had nearly completed its shift to the right.

But Edwards proved to be a skillful campaigner, in step with right-of-center voters with his opposition to abortion and his support for gun ownership and hunting. During the campaign, he benefited when his three Republican challengers tore each other up, leaving the longtime favorite, then-U.S. Sen. David Vitter, battered and bruised by a prostitution scandal when he faced Edwards in the runoff.

After winning the election, Edwards won bipartisan approval of the Legislature for a temporary 1-cent increase in the state sales tax — and a .45-cent renewal of that tax two years later — to eliminate the state’s budget problems. He narrowly won reelection in 2019.

“Edwards was very thoughtful, very concerned and very willing to do what he thought was correct,” said Jim Richardson, an LSU economist who advised lawmakers on the state’s finances. “If he got backlash, he accepted that. He played the only hand he could play, and he played it well.”

Over his eight years in office, he and state lawmakers invested more in early childhood education than ever before, paid down state debt and directed money to build new bridges over the Calcasieu River in Lake Charles and the Mississippi River in Baton Rouge. He also got a big lift from Washington, with Louisiana receiving tens of billions of dollars in post-pandemic aid passed by the Biden administration and the Democratic Congress.

Citing a need to end giveaways that he said needlessly hurt local governments, Edwards scaled back a lucrative tax break for manufacturing companies in the Industrial Tax Exemption Program that initially produced a torrent of criticism. Landry has since pledged to keep the changes, which give local governments a say in whether to grant the tax breaks.

In what may be his most transformative move, Edwards has put Louisiana on a path to achieve net zero emissions by 2050, arguing that renewable energy creates jobs, diversifies the oil and gas economy and helps Louisiana do its part to limit global warming.

Roadblocks faced

But he had trouble with other policy initiatives. The Republican-controlled Legislature stymied his efforts to raise the state minimum wage, close a gender pay equity gap that is the highest in the country and raise teacher pay high enough to reach the average salary in southern states.

He also suffered other failures. Republican lawmakers rejected the Democrat who he tried to install as speaker when he took office. Landry, local district attorneys and the state pardon board killed his effort this year to have inmates on death row be given life sentences instead. Edwards badly over-promised the number of jobs that DXC, a technology company, would create in New Orleans. The most recent census figures show that Louisiana’s population growth continues to lag behind that of the country and especially neighboring states.

Several categories of Louisiana’s most vulnerable citizens — juvenile offenders, children needing protection from abusive adults and inmates due to be released — didn’t consistently receive the attention they needed.

Edwards also had to spend considerable time in crisis mode, managing the state’s response to powerful hurricanes, devastating floods and, above all, the worst pandemic to hit the United States in 100 years.

His worst day as governor, Edwards said in a recent interview, occurred on July 17, 2016. He and his wife Donna Edwards were getting ready for church that day when he got word that a crazed gunman had shot six Baton Rouge police officers, nearly two weeks after police killed Alton Sterling and triggered days of unrest in Louisiana’s capital.

As he did during the national disasters, Edwards relied on his training at West Point and as an Army officer to project calm and authority, and the crisis passed.

After he leaves office on Jan. 8, Republicans will hold all statewide offices, and, compared to when he took office, there will be eight fewer Democrats in the 105-member House and three fewer Democrats in the 39-member Senate.

The Deep South’s only Democrat governor pushes back on critics who say he is to blame.

“When you’re a Democratic governor, you can either put your focus on the word ‘Democrat’ or you can put it on ‘governor,’” Edwards said during a recent meeting of The Times-Picayune | The Advocate editorial board. “I chose to put it on ‘governor.’ If I’m out there campaigning out there against Republicans every day, while I’m simultaneously asking them to support what I’m doing, I promise you that I can’t come into this room and point to all the areas where we’ve demonstrably improved the state of Louisiana.”

What’s next

Edwards fears that Landry will try to undo one achievement: the package of laws that Edwards and legislators passed in 2017 that have shortened some prison sentences, kept certain nonviolent offenders out of prison, expanded eligibility for parole and provided more money to educate and train ex-offenders. The bipartisan package sought, but failed, to end Louisiana’s status as the country’s biggest jailer on a per capita basis, though data shows it lowered the state’s prison population.

“For as long as I can remember, Louisiana reflexively responded to an increase in crime by putting more people in prison and keeping them there longer,” he said. “We’ve never been made safer as a result of that. There is no data to suggest that an increase in crime here was because of the reforms.”

On the flight to Shreveport earlier this month, Edwards said he would have run for reelection if the state constitution permitted him to seek a third term.

“If you could and you don’t, it’s akin to quitting,” he said over the thrum of the small plane’s motor. “I’ve never quit anything in my life.”

And if he had run against Landry?

“I would have beaten him,” he said flatly.

Instead, Edwards, 57, will return to his home in the Tangipahoa Parish hamlet of Roseland and practice law with an office in Hammond.

“I really need to put some acorns away for me and Donna,” he said, noting that his wife spent the past eight years working full-time as a volunteer first lady, and they put three children through college in recent years.

Asked if he could foresee himself working for a company to promote renewable energy projects, Edwards said he could.

“It’s something you can do and achieve that rare mix of something that would be very interesting and exciting and potentially rewarding financially,” he said. “I believe in the energy transition.”

Edwards won’t rule out running for office again one day.

“I hope that Jeff Landry is wildly successful,” he said. “I hope our state is doing better than ever, and it would never occur to me to run. That’s what I hope. That’s what I pray for. But it’s not what I believe is most likely to happen.”