Social media has been abuzz for days with rumors of an East Coast snowstorm. That’s nothing unusual — it seems the internet is always conjuring up hypothetical storms or high-impact blizzards, few of which ever materialize.

Except this time there’s actually a chance, and a decent one. The odds of a disruptive snowstorm are increasing for parts of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast this weekend, especially for the interior and Appalachian Mountains. Along the Interstate 95 corridor, it might be a toss-up between rain and snow, but with growing snow chances as one heads north of the Mid-Atlantic.

Wildcards abound, making it impossible to offer specific forecasts this far out. Details will become clearer by Wednesday and especially Thursday, when it may be possible to start forecasting when precipitation will start and stop at specific locations, who will see rain versus snow, and how much will fall.

Still, some of the most populous cities in the country could be in line for accumulating snow or a mix of snow, sleet and rain.

Here we identify a few plausible scenarios, what we’re watching, and what the effects may be.

The basic setup

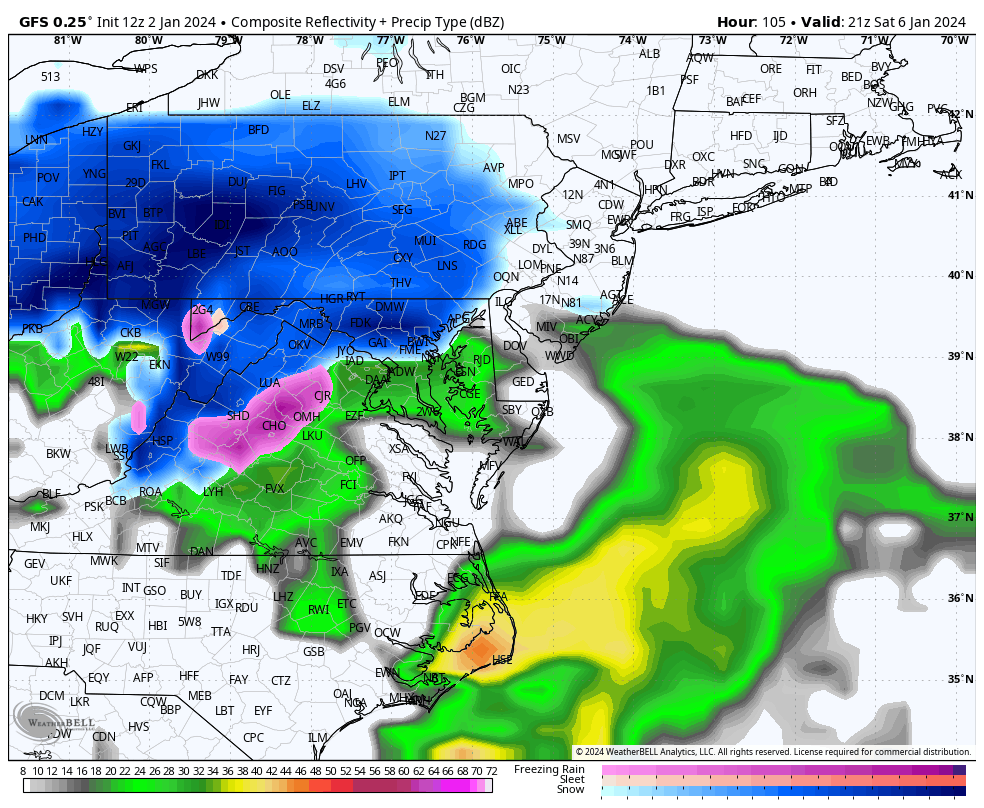

At present, a “shortwave,” or a pocket of high-altitude cold air, low pressure and spin, is located south of the Aleutian Islands in the northeast Pacific Ocean. That system will dive southeast over the Lower 48 in the coming days, bringing rain to the southern Plains and Deep South on Friday, then generating a zone of low pressure near the Mid-Atlantic coast over the weekend.

That low-pressure system will ride north parallel to the Eastern Seaboard. To the east, well offshore, a tongue of warm, humid air will wrap north, fueling thunderstorms over the Gulf Stream. Some of that moisture will pinwheel back to the west and northwest around the low-pressure center, falling as snow on the storm’s cold side. That will be at least 50 to 100 miles west of the storm’s path.

Exactly how near to or far from the coast the low-pressure system tracks will have major implications for snowfall. Low pressure tracking right along the coast or inland will draw enough warm air west for more rain along the I-95 corridor, with heavy snow mostly confined to the mountains. But if the low tracks a bit farther offshore, it could allow enough cold air to remain in place for the first significant snow in a couple of years for Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia and New York.

Impacts

The worst of the storm will come through Saturday into Sunday. For the Piedmont of western North Carolina, it will begin before dawn Saturday. Then between early morning and early afternoon, it will expand through the Mid-Atlantic, reaching the Northeast on Saturday evening.

As the I-95 corridor from Washington to New York could well straddle the rain-snow line, possible scenarios include mostly rain, mostly snow or a messy mix of precipitation. That’s why specific snow totals are impossible to project this far in advance.

Providence, R.I.; Boston; and Portland, Maine, have better snow prospects compared to I-95 cities to the south.

The heaviest snowfall, potentially exceeding a foot, will probably fall in the Appalachians, where confidence in the forecast is higher.

What we know

Models are in unusually strong agreement that a low-pressure system will form somewhere near the Mid-Atlantic coast on Saturday. With sufficient moisture, it stands to reason that significant accumulations of rain, snow or both are likely in a swath from Virginia to Maine.

We know that the air ahead of the storm won’t be especially cold, meaning this won’t be a slam-dunk snowstorm. What’s most probable is that snow will fall inland, especially at higher elevations where it’s colder.

To the bane of forecasters, the forecast for what types of precipitation will fall over major cities is highly uncertain, especially from Washington to New York.

What we don’t know

The parent upper-air disturbance, which remains offshore, has yet to move over the Pacific Northwest. Once it does, the National Weather Service will be able to launch weather balloons into it. That’s how they’ll ascertain critical data about its shape, strength and movement, which will be fed into computer models to better simulate the upcoming storm.

We don’t know where exactly the storm will track, and subsequently cannot forecast where the rain-snow line will be. That means anyone forecasting specific rain or snow totals for large population centers along I-95 is basically guessing.

We also don’t know how strong the “50-50 low” — or zone of low pressure near 50 degrees north latitude and 50 degrees west longitude near Newfoundland — will set up. This low is responsible for swirling cold air southward ahead of the storm, in conjunction with an area of high pressure in southeast Canada. Models don’t project this pair of pressure systems to become particularly strong, limiting the amount of cold air. That’s why snow totals may not be big east of the mountains in the Mid-Atlantic.

We also don’t know where the western edge of the precipitation shield will become established. In storms like this, the western edge is usually razor sharp. It’s still unclear exactly where substantial snowfall will cut off in northern and western New England.

The bottom line

Putting it all together, it’s too early to know exactly what will transpire with this storm.

For many, this is the first formidable snow chance of the past two-plus years, following lackluster back-to-back winters.

We’ll continue to share updates and fine tune the latest forecasts.