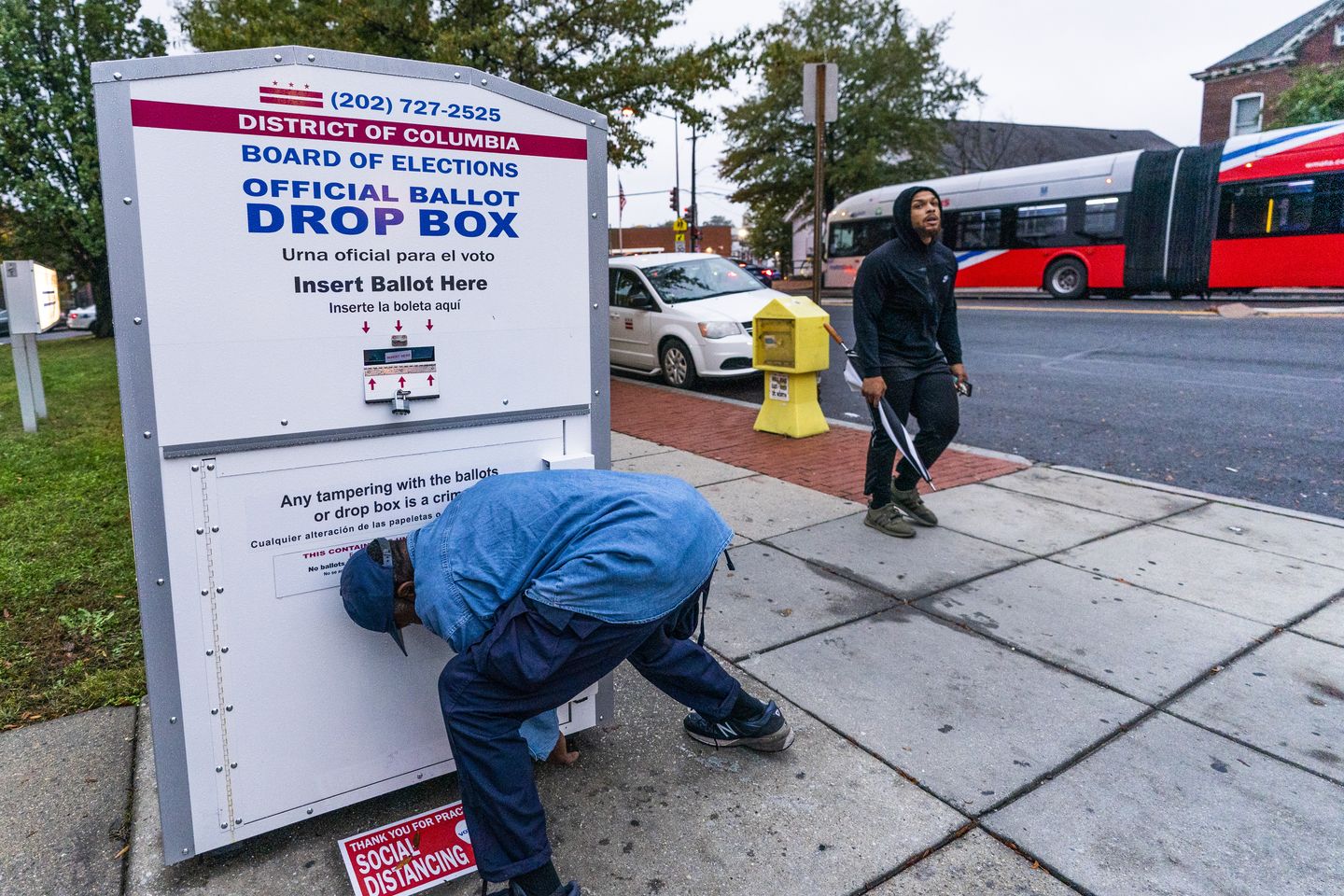

The District of Columbia is preparing for the country’s biggest experiment yet with noncitizen voting, which has been on the books for nearly a year and will go live in its first election in 2024.

As of mid-December, the city said three people have registered, all of them showing up in person to do so. Officials hope for more interest when it opens online registration to noncitizens next year.

Jurisdictions across the country are testing the waters for allowing noncitizens, including in many cases illegal immigrants, to cast ballots in local elections. But for the most part, they’re finding scant interest among those they’re trying to entice into the polling booth.

San Francisco made waves in 2016 when it allowed noncitizens to start voting in local school elections.

In the last go-around, in 2022, about 300,000 residents cast ballots. Just 72 of them were through the noncitizen system.

Maryland has the most jurisdictions practicing noncitizen voting, though they are all small cities or villages.

Takoma Park, just across the line from Washington, is the grandfather of the idea, having just celebrated 30 years of allowing noncitizen voting.

In 2017, the city had 347 noncitizens on its rolls and 72 cast ballots — a turnout of about 20%. That was the last year the city reported the data. It now shrouds the data in a joint figure along with same-day registrants and voters ages 16 and 17, who are also allowed to vote in city affairs.

In Vermont, Winooski adopted noncitizen voting in 2022. One election for city council seats did attract some turnout from the new “all-resident” voter list, but another election deciding a water district bond issue drew no all-resident voters.

City Clerk Jenny Willingham said voters who sign up on the all-resident list must answer two questions: They must affirm they will be 18 by election day, and that they are residents on a permanent or indefinite basis.

She said they figure there are perhaps 600 noncitizen residents out of about 8,000 people in the city.

“This is an initiative in our city and I want to encourage people to vote, I’d like to get those numbers up more,” she said. “Right now there’s 61 and I’m hoping for more.”

The system is supposed to be for legal immigrants, but like so much else in voting, that’s left up to the residents themselves to self-certify. Ms. Willingham said she doesn’t have the bandwidth to verify the applications and trusts the oath the voters take saying they are qualified.

Her office does warn applicants that the voting records are public records and available for inspection, which could include immigration officials. Ms. Willingham said one group showed up for an information session and when that part of the application was read to them by an interpreter, they backed out.

While it’s a heated issue now, noncitizen voting has a lengthy history in the U.S.

In the 19th century, it was known as alien suffrage, and was quite common, with more than 20 states allowing it in the years before 1900. Anti-immigrant sentiment fueled a retrenchment and Arkansas became the last state to end the practice in 1926.

Now, nearly a century later, the idea is seeping back, pushed by immigrant-rights advocates who argue noncitizens often have children in schools, pay taxes and use services, and deserve a say in how those decisions are made.

J. Christian Adams, who runs the voter watchdog Public Interest Legal Foundation and is challenging the New York noncitizen voting law, said he figures the low numbers are temporary and advocates are downplaying registration to try to legitimize the practice.

“The key for them now is to open up the gate before they start cramming the sheep through,” he said. “Don’t be fooled into thinking this isn’t a big deal because only a couple people in Takoma have registered.”

At the state level, proposals to limit voting only to citizens usually pass with strong support when put to voters. In 2022, both Louisiana and Ohio passed bans on noncitizen voting, with roughly three-fourths of voters backing the bans.

At the same time, when voters in deep-blue cities and towns have been asked, they have usually embraced noncitizen voting. Burlington, Vermont, approved noncitizen voting with two-thirds of voters in favor. Greenbelt, Maryland, adopted noncitizen voting in a referendum in November with more than two-thirds of voters in support.

But in Rockville, Maryland, the idea was defeated with 64% against it. An even larger 69% voted against allowing residents ages 16 and 17 to vote.

Federal law explicitly bans noncitizens from voting in federal elections, so jurisdictions that want to allow the practice for their elections must maintain separate lists.

Some of the cities worried that immigration enforcement officers might scour the lists, which are public records, seeking deportation targets, though several local election officials said they’ve yet to have that happen.

Still, cities have come up with a defense.

Hyattsville, in Maryland, pointedly corrects those who call its list a noncitizen voting roll, saying they use the term “city-only.”

Clerk Laura Reams said there may be some citizens who are eligible to vote in all elections but for whatever reason didn’t want to register with the state and did choose to register and vote in the city contests. So their names could appear alongside noncitizens in the city-only list.

Hyattsville, which like Takoma Park is just across the border from Washington, said it has about 230 voters on the city-only list. Some 17% turned out in the city elections earlier this year, or about 40 voters, out of a total turnout of 667.

Takoma Park also burrows its noncitizen voting figure inside its same-day registrant and younger voter data.

The District of Columbia will be a major test for advocates.

The city will allow anyone who’s been a resident for 30 days to register and cast a ballot.

Critics say that could include not only illegal immigrants but even foreign diplomats for adversary governments. They will only be voting on city issues, however.

An attempt to derail the effort was launched last year in Congress, which has a veto over the capital city’s legislation. It cleared the House on a 260-162 vote, with 42 Democrats joining Republicans in support.

That suggested a real chance to block the city, but senators never got around to taking up the issue, allowing the ordinance to take effect.

The Center for Immigration Studies calculated that 42,000 noncitizens, including perhaps 20,000 illegal immigrants, would be eligible.

Copyright © 2024 The Washington Times, LLC.

Click

here for reprint permission.

Please read

our comment policy before commenting.